|

|

|

Heinz

by Teresa Gleadowe

from Southern Arts

No. 23 - March 1976

| |

|

Heinz Henghes

came to Winchester in 1964 and worked for nine years at Winchester

School of Art. He joined the school as Head of Fine Art and it was

largely through his efforts that Winchester was granted Diploma Status

in Painting and Sculpture. Later he resigned as Head of Fine Art to

become Head of the Sculpture School. He retired in 1973 and at that

time spoke with some acerbity about the role of the artist / teacher:

'Teaching of art is better for the students than for the teachers

- the need to provide answers and explain art forces it into a level

of intellectual consciousness and the making of art is very little

to do with the intellect'. But he was passionately interested in the

art school system, believing it to be the only means to a broadly

'humanist' education and an essential alternative to the specialized

Curricula of the universities. His teaching was aimed not at training

'artists' but at preparing people to 'see' and `feel' their way through

life.

Heinz was a natural teacher and I and many of his friends in Winchester

(who were not even formally his students) learned from him throughout

the time we knew him. What we learned was not to do with academic

knowledge but with a totality of experience which he communicated

through everything he did and from which his work was drawn. 'I am

born lucky, born to confront and affront the totality of life and

to suck from it the personal essence of what I can take and use and

have and hold and turn into ... whatever ...drawings ...carvings ...

documents of the pleasure of being alive and the rightness of being'.

|

|

|

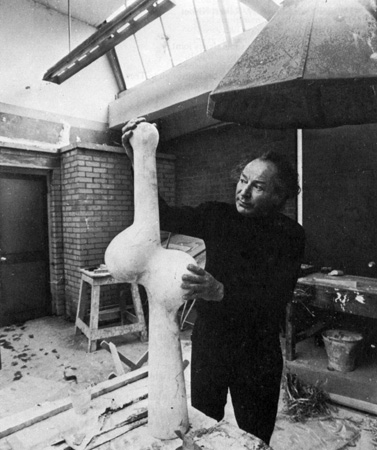

Heinz Henghes in Winchester.

Photo Pete Wallis |

|

I met Heinz when I joined Southern Arts in 1972. He had already contributed

to the organisation of a major sculpture show Ten Sculptors, Two

Cathedrals, sponsored by the association, and was later to contribute

to the exhibition Sculpture at South Hill Park. But my memories

are not of exhibitions or indeed of any one piece of sculpture. In

an interview in Southern Arts Heinz described a work of art

as 'a wide open window onto a full world' and the objects he made

were all intended in some way to sharpen one's sense of the matter

of life. And equally the way he lived, fed the work. My memories are

of his cluttered studio, under the shadow of the cathedral -where

he worked and talked and invented extraordinary concoctions from the

grime of a filthy stove. His house on a hillside in the Dordogne where

he watched warily the changing of the seasons:

| |

|

|

'Autumn is holding its breath and the leaves are turning and I know what will happen ... from one day to the next there will be a great storm and it will strip the leaves and the nuts and leave the hills burning red and gold ...' But I also remember arguments, an absurd recurring one about the cathedral - Heinz describing it as an 'empty old barn, squat as a toad', unworthy of comparison with the cathedrals of France and Germany. And I remember his stubbornness and cussedness (it would be uncharitable to forget these things).

Heinz was not a life-long countryman and his enjoyment of the country

and of the house in the Dordogne to which he finally retired was that

of a traveller finding home. He was not sentimental or romantic about

the country and the creatures which inhabited it - he knew that their

purpose was to survive and he too was a survivor. There was between

them a kind of force and mostly this was peaceful. Not always so:

I remember a day when war broke out between him and the lone cricket

that sat in the garden's largest tree, with Heinz shaking the tree

to bring the cricket down, and the cricket outwitting him to the end.

Heinz compared himself to Voltaire's Candide, settling at last to

cultivate his garden. His more exotic adventures were past when I

met him-and I knew them only as stories - childhood in Germany. America

in the 20s. Italy with Ezra Pound in the 30s. Paris and finally London

to show at Peggy Guggenheim's gallery. And the time of experimenting

with new materials and styles was also past - increasingly he returned

to direct carving in stone and shapes derived from nature and prehistory.

'I have given myself to the reassertion by the simplest physical means

possible (carving stone) of values which reassert the power and the

glory of the ancient gods ... I am, I have no other means than to

be, an agent, a perpetrator of the archaic thing. The fossil, the

absolute and the immutable image'.

| |

|

Biography Techniques Exhibitions

& Collections

|

|

|

|

|